The cavalier King Charles spaniel breed

is brachycephalic

The

cavalier King Charles spaniel is a brachycephalic breed. While its

muzzle may not be as short as a few other breeds, brachycephalic means a

whole lot more than just a flat face. The cavalier, as a breed, suffers

from several classic brachycephalic conditions, including

brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome

(BAOS), an

elongated soft palate,

Canine

Chiari Malformation,

stenotic nares,

everted

laryngeal saccules, laryngeal

and pharyngeal collapse, and

sleep disorded

breathing.

The

cavalier King Charles spaniel is a brachycephalic breed. While its

muzzle may not be as short as a few other breeds, brachycephalic means a

whole lot more than just a flat face. The cavalier, as a breed, suffers

from several classic brachycephalic conditions, including

brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome

(BAOS), an

elongated soft palate,

Canine

Chiari Malformation,

stenotic nares,

everted

laryngeal saccules, laryngeal

and pharyngeal collapse, and

sleep disorded

breathing.

What It Is

Brachycephaly is the name given to describe dogs with shortened facial skeletons. It includes both the skull and its muzzle. It is a heritable developmental defect.

The term "brachycephalic" or "brachiocephalic" means short-headed and refers to dogs with a shortened cranium (the bones that house the brain). Most brachycepahic dogs have short muzzles and flat faces and noses which tip back (airorhynchy) and a shorted lower jaw, but not necessarily.

"Brachy" means short and "cephalic" means head. This shortening refers only to the skull and bones and not to the soft tissues -- the tongue, soft palate, nasal passages, and the brain. Thus, the throat and breathing passages in brachycephalic dogs often are undersized or flattened. The head's soft tissues are not proportionate to the shortened nature of the skull, and the excess tissues tend to increase resistance to the flow of air through the upper airway (nostrils, sinuses, pharynx and larynx).

It is characteristic of many familiar toy dog breeds, and includes the cavalier King Charles spaniel in most all cases. This defect is somewhat more apparent in a few other breeds: the English bulldog, pug, Boston terrier, and Pekingese, in particular.

Many CKCS fanciers have argued that the cavalier is not brachycephalic because its muzzle length is longer than that of my obvious brachycephalic breeds, pugs being an example. They are mistaken. They fail to consider the history of the breed, coming from the classically brachycephalic King Charles spaniel (English toy spaniel) and the resulting jumble of soft tissue organs, including the brain, eyes, nasal passages, airways, and soft palate, as well as the jaw.

Until 2011, there had been some dispute among researchers as to whether the cavalier King Charles spaniel is a brachycephalic breed or a mesaticephalic (or mesocephalic) breed. However, in an April 2011 study, the researchers concluded that the CKCS was brachycephalic but that it had a wider braincase in relation to length than in other brachycephalic breeds. In that article, the investigators cleared the air:

"Although the CKCS has been derived from the brachycephalic King Charles Spaniel, the CKCS has not been confirmed to be a member of a specific morphologic group. The phenotype of the CKCS does not seem to be brachycephalic at first glance. Compared with most brachycephalic breeds, the CKCS has a nose that is straight and well developed and inferior prognathism is seldom seen. However, there areindications from skull morphology that the CKCS is indeed a brachycephalic breed. A miniscule or absent frontal sinus and ventral orientation of the olfactory bulbs, both features of brachycephalic conformation, are present in the CKCS. Our purpose was to determine the general skull type of the CKCS based on classic cephalometric measurements and to validate the classic measurements against dogs with other skull types.

"Brachycephalic traits include a shortened face, a rostrally elevated palate, an arched zygomatic apophysis, forward facing eyes, maxillary hypogenesis, aberrant conchal growth, dorsally rotated teeth, and breathing problems. Brachycephaly, however, also involves structural alteration of the neurocranium. The braincase is shortened and widened in brachycephalic dogs. Premature fusion of cranial base sutures is hypothesized to be the primary cause for the changes in skull morphology that lead to a reduction of the longitudinal axis of the cranial base. However, the force of the developing brain extends the skull along the lines of least resistance, laterolaterally, leading to a skull with increased width. This is reflected by the high cranial index of brachycephalic dogs in comparison to mesaticephalic dogs. ... Morphologic parameters of the head of the CKCS clearly differs from the mesaticephalic head type and the CKCS must be regarded as brachycephalic. In fact, the higher CI and LB3 in combination indicate an even shorter longitudinal axis of the neurocranium in comparison to the other brachycephalic dogs in our study. This must be considered when comparing specific features of the CKCS skull that may cause the deviation of the cerebellum into the foramen magnum or other morphologic changes." (Emphasis added.)

See also this September 2012 article: "Amongst brachycephalic dog breeds the CKCS has been identified as having an extremely short and wide braincase."

See also, this September 2013 article: "The Cavalier King Charles Spaniel has been recognized to be more brachycephalic than other brachycephalic dog breeds."

See also, this January 2017 article: "Although the CKCS is recognised as having a brachycephalic skull, facial length is very varied in the breed, with the muzzle becoming fashionably shorter and more dorsally rotated (airorhynchy) in the last decade."

See also this July 2017 article: " Cavalier King Charles Spaniels represent a unique subset of brachycephalic animals as they were found to have significantly flatter tympanic bullae (defined by width: height ratios) than other brachycephalic breeds."

See also this March 2018 article: "In the CKCS, risk of SM has been shown to be associated with increased brachycephaly with rostrocaudal doming i.e. a heightened cranium that slopes caudally and reduced skull base due to craniosynostosis or premature skull suture closure."

See also,this June 2018 abstract: "Cavalier King Charles Spaniels are classified as a brachycephalic breed and this classification is considered important in morphometric analyses of their skull and brain."

RETURN TO TOP

Evolution of the CKCS

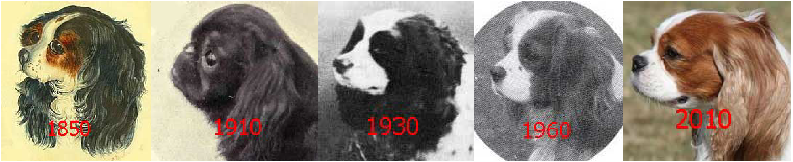

The evolution of the modern-day cavalier King Charles spaniel is somewhat unique. While the ancestors of most all currently brachycephalic breeds had significantly longer muzzles, the most recent ancestors of the CKCS had extremely short ones. Up until the late 1800s and early 1900s, most of the cavalier’s ancestors had relatively long muzzle lengths. (Such as the 1850 King Charles spaniel below.) Then, beginning in the 1890s through the 1920s, the breed standard called for their snouts to be bred much shorter. By 1910, champion King Charles spaniels (see one such 1910 champion below) had snouts no longer than those of today's pugs and French bulldogs.

A consequence of this evolution was first to create very short-muzzled dogs and then produce from those dogs a longer-muzzled version which became the cavalier. This amounted to an accordion affect which did not straighten out the damage done when the King Charles spaniel breed standard demanded much shorter muzzles.

RETURN TO TOP

Calculating Brachycephaly

There are two objective mathematical methods of calculating brachycephaly in individual dogs. The Cephalic Index and the Cranio-Facial Index are described in detail below. Despite research concluding that, as a breed, the cavalier King Charles spaniel is in the brachycephalic category, that does not mean that every cavalier necessarily is brachycephalic according to standard ways to measure their heads.

As noted in the Evolution of the CKCS section above, cavaliers descended from an obviously brachycephalic breed with much shorter heads and muzzles. Some CKCS today may have significantly longer heads and snouts than others. Nevertheless, because of their ancestors, they too are brachycephalic. Developing those longer heads did not un-jumble the conseequences of how their King Charles spaniel (English toy spaniel) ancestors were bred.

As observed in the foregoing April 2011 article, some cavaliers may not be brachycephalic as determined by these objective mathematical formulas, but nonetheless are brachycephalic because of their internal skull morphology. As the article states:

"A miniscule or absent frontal sinus and ventral orientation of the olfactory bulbs, both features of brachycephalic conformation, are present in the CKCS. ... Brachycephalic traits include a shortened face, a rostrally elevated palate, an arched zygomatic apophysis, forward facing eyes, maxillary hypogenesis, aberrant conchal growth, dorsally rotated teeth, and breathing problems. Brachycephaly, however, also involves structural alteration of the neurocranium. ... Morphologic parameters of the head of the CKCS clearly differs from the mesaticephalic head type and the CKCS must be regarded as brachycephalic. In fact, the higher CI and LB3 in combination indicate an even shorter longitudinal axis of the neurocranium in comparison to the other brachycephalic dogs in our study. This must be considered when comparing specific features of the CKCS skull that may cause the deviation of the cerebellum into the foramen magnum or other morphologic changes." (Emphasis added.)

There are a couple of objective ways to determine if an individual dog is brachycephalic or not:

• Cephalic Index: The width of the cranium, multiplied by 100, is divided by its length. Calipers are used for accurate measurements. The resulting score is a percentage. In this black-&-white photo of thehead of a cavalier (right), the width is the yellow line and the length is the red line. Using the Cephalic Index method, a dog is considered to be brachycephalic if the resulting Cephalic Index ratio is over 60%.

• Cranio-Facial Index: The width of the cranium is divided by the length of the cranium and muzzle. In this color photo (right) of the dog, the red line is the same red line as in the black-&-white photo. The blue arrow line is the length of both the cranium and muzzle. A resulting score of 0.5 would mean that muzzle represents 1/3 of the length of the head and that the dog. Dogs with a cranio-facial index of less than 0.5 are considered to be brachycephalic.

The combinations of various head-related health issues of the CKCS breed, outlined below, confirm that it is brachycephalic, regardless of whether or not individual cavaliers calculate as being so from a mathematical index standpoint.

RETURN TO TOP

Associated Health Problems

Brachycephaly is associated with several health problems in the cavalier, including:

• Brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome (BAOS)

• Chiari-like malformation (Canine Chiari) and syringomyelia

• Hydrocephalus and ventriculomegaly

• Intervertebral disc disease

• Dental and gum disorders (periodontal disease)

• Several eye disorders, including dry eye syndrome and corneal-related

• Some gastrointestinal disorders, especially esophagus-related

Each one of these disorders is discussed at length on its own webpage, which is linked in the list above.

RETURN TO TOP

Veterinary Resources

Cephalometric Measurements and Determination of General Skull Type of Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. M. J. Schmidt, A. C. Neumann, K. H. Amort, K. Failing, M. Kramer. Vet. Rad. & Ultra, 26 Apr 2011. Quote: The general skull morphology of the head of the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS) was examined and compared with cephalometric indices of brachycephalic, mesaticephalic, and dolichocephalic heads. ... Although the CKCS has been derived from the brachycephalic King Charles Spaniel, the CKCS has not been confirmed to be a member of a specific morphologic group. The phenotype of the CKCS does not seem to be brachycephalic at first glance. Compared with most brachycephalic breeds, the CKCS has a nose that is straight and well developed and inferior prognathism is seldom seen. However, there are indications from skull morphology that the CKCS is indeed a brachycephalic breed. A miniscule or absent frontal sinus and ventral orientation of the olfactory bulbs, both features of brachycephalic conformation, are present in the CKCS. Our purpose was to determine the general skull type of the CKCS based on classic cephalometric measurements and to validate the classic measurements against dogs with other skull types. ... Measurements were taken from computed tomography images. Defined landmarks for linear measurements of were identified using three-dimensional (3D) models. The calculated parameters of the CKCS were different from all parameters of mesaticephalic dogs but were the same as parameters from brachycephalic dogs. However, the CKCS had a wider braincase in relation to length than in other brachycephalic breeds. ... Brachycephalic traits include a shortened face, a rostrally elevated palate, an arched zygomatic apophysis, forward facing eyes, maxillary hypogenesis, aberrant conchal growth, dorsally rotated teeth, and breathing problems. Brachycephaly, however, also involves structural alteration of the neurocranium. The braincase is shortened and widened in brachycephalic dogs. Premature fusion of cranial base sutures is hypothesized to be the primary cause for the changes in skull morphology that lead to a reduction of the longitudinal axis of the cranial base.18,23,24 However, the force of the developing brain extends the skull along the lines of least resistance, laterolaterally, leading to a skull with increased width. This is reflected by the high cranial index of brachycephalic dogs in comparison to mesaticephalic dogs. ... Morphologic parameters of the head of the CKCS clearly differs from the mesaticephalic head type and the CKCS must be regarded as brachycephalic. In fact, the higher CI and LB3 in combination indicate an even shorter longitudinal axis of the neurocranium in comparison to the other brachycephalic dogs in our study. This must be considered when comparing specific features of the CKCS skull that may cause the deviation of the cerebellum into the foramen magnum or other morphologic changes. ... Studies of the etiology of the chiari-like malformation in the CKCS should therefore focus on brachycephalic control groups. As Chari-like malformation has only been reported in brachycephalic breeds, its etiology could be associated with a higher grade of brachycephaly, meaning a shorter longitudinal extension of the skull. This has been suggested for other breeds.

Volume reduction of the jugular foramina in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels with syringomyelia. Martin Jürgen Schmidt, NeleOndreka1,Maren Sauerbrey, Holger Andreas Volk, Christoph Rummel, Martin Kramer. BMC Veterinary Research. September 2012; doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-158. Quote: Background: Understanding the pathogenesis of the chiari-like malformation in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS) is incomplete, and current hypotheses do not fully explain the development of syringomyelia (SM) in the spinal cords of affected dogs. This study investigates an unconventional pathogenetic theory for the development of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure waves in the subarachnoid space in CKCS with SM, by analogy with human diseases. In children with achondroplasia the shortening of the skull base can lead to a narrowing of the jugular foramina (JF) between the cranial base synchondroses. This in turn has been reported to cause a congestion of the major venous outflow tracts of the skull and consequently to an increase in the intracranial pressure (ICP). Amongst brachycephalic dog breeds the CKCS has been identified as having an extremely short and wide braincase. ... Recently the CKCS has been shown to have an extremely high braincase length-width ratio (cranial index) compared to other brachycephalic dogs. ... A stenosis of the JF and a consequential vascular compromise in this opening could contribute to venous hypertension, raising ICP and causing CSF jets in the spinal subarachnoid space of the CKCS. In this study, JF volumes in CKCSs with and without SM were compared to assess a possible role of this pathologic mechanism in the development of SM in this breed. Results: Computed tomography (CT) scans of 40 CKCSs > 4 years of age were used to create three-dimensional (3D) models of the skull and the JF. Weight matched groups (7–10 kg) of 20 CKCSs with SM and 20 CKCSs without SM were compared. CKCSs without SM presented significantly larger JF -volumes (median left JF: 0.0633 cm3; median right JF: 0.0703 cm3; p < 0.0001) when compared with CKCSs with SM (median left JF: 0.0382 cm3; median right JF: 0.0434 cm3; p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference between the left and right JF within each group. Bland-Altman analysis revealed excellent reproducibility of all volume measurements. Conclusion: A stenosis of the JF and consecutive venous congestion may explain the aetiology of CSF pressure waves in the subarachnoid space, independent of cerebellar herniation, as an additional pathogenetic factor for the development of SM in this breed.

Comparison of Closure Times for Cranial Base Synchondroses in Mesaticephalic, Brachycephalic, and Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Dogs. Martin J. Schmidt, Holger Volk, Melanie Klingler, Klaus Failing, Martin Kramer, Nele Ondreka. Vet.Radiology & Ultrasound. Sept. 2013;54(5):497-503. Quote: premature closure of cranial base synchondroses has been proposed as the mechanism for brachycephaly in dogs and caudal occipital malformation syndrome (COMS) in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. The purpose of this retrospective study was to compare times of closure for cranial base synchondroses in mesaticephalic, brachycephalic, and Cavalier King Charles Spaniel dogs. ... The Cavalier King Charles Spaniel has been recognized to be more brachycephalic than other brachycephalic dog breeds. ... Cranial magnetic resonance imaging studies were retrieved for client-owned dogs less than 18 months of age. Breed, age, skull conformation, and the open or closed state of cranial base synchondroses were independently recorded by two observers. For dogs with a unanimous observer agreement, regression analysis was used to test effects of age and gender on the open or closed status of synchondroses and differences between groups. A total of 174 dogs were included in MRI interpretations and 165 dogs were included in the regression analysis. Statistically significant differences in closure time of the spheno-occipital synchondrosis were identified between brachycephalic and mesaticephalic dogs (P = 0.016), Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and mesaticephalic dogs (P < 0.0001), and Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and brachycephalic dogs (P = 0.014). Findings from the current study supported the theory that morphological changes leading to the skull phenotype of the Cavalier King Charles Spaniels could be due to an earlier closure of the spheno-occipital synchondrosis.

Syringomyelia: determining risk and protective factors in the conformation

of the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel dog.

Thomas

J. Mitchell, Susan P. Knowler, Henny van den Berg, Jane Sykes, Clare

Rusbridge. Canine Genetics & Epidemiology. July 2014. Quote: Syringomyelia

(SM) is a painful condition, more common in toy breeds, including the

Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS), than other breeds. In

these toy breeds, SM is usually secondary to a specific malformation of the

skull (called Chiari-like Malformation, CM for short). ... The

Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS) is a toy breed dog,

popular as a companion and also in the conform- ation showing fancy

with 5,970 and 39,670 new registra- tions in 2012 with the Kennel

Club (KC) and worldwide respectively [1]. The CKCS,

like many brachycephalic toy breeds, is predisposed to

syringomyelia, a condition where fluid filled cavities (syrinxes)

develop within the central spinal cord. ,,, There has been debate

as to whether head shape is related to CM/SM, especially as some humans have

similar characteristic facial and skull shapes, and what this may be.

Identifying a head shape in dogs that is associated with these diseases

would allow for selection away from these conditions and could be used to

further breeding guidelines. 133 dogs were measured in several countries

using a standardised 'bony landmark' measuring system and photo analysis by

trained researchers. This paper describes two significant risk factors

associated with CM/SM in the skull shape of the CKCS:

extent of brachycephaly (the broadness of the cranium (top of skull)

relative to its length) and distribution of doming of the cranium. The study

showed that having a decreased cephalic index (less brachycephaly) was

significantly protective. Further to this, more cranium at the back of the

head (caudally) relative to the amount at the fro nt of the head (rostrally)

was significantly protective against disease development. This was shown at

three and five years of age, and also when comparing a sample of “SM clear”

individuals over five years to those affected under three years. This study

suggests that brachycephaly, with resulting rostrocaudal doming, is

associated with CM/SM. These results could provide a way for selection

against the risk head shape in the CKCS, and thus enable a

reduction in CM/SM incidence. Studying other breeds in which CM free

individuals are more frequent may validate this risk phenotype for CM too.

Thomas

J. Mitchell, Susan P. Knowler, Henny van den Berg, Jane Sykes, Clare

Rusbridge. Canine Genetics & Epidemiology. July 2014. Quote: Syringomyelia

(SM) is a painful condition, more common in toy breeds, including the

Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS), than other breeds. In

these toy breeds, SM is usually secondary to a specific malformation of the

skull (called Chiari-like Malformation, CM for short). ... The

Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS) is a toy breed dog,

popular as a companion and also in the conform- ation showing fancy

with 5,970 and 39,670 new registra- tions in 2012 with the Kennel

Club (KC) and worldwide respectively [1]. The CKCS,

like many brachycephalic toy breeds, is predisposed to

syringomyelia, a condition where fluid filled cavities (syrinxes)

develop within the central spinal cord. ,,, There has been debate

as to whether head shape is related to CM/SM, especially as some humans have

similar characteristic facial and skull shapes, and what this may be.

Identifying a head shape in dogs that is associated with these diseases

would allow for selection away from these conditions and could be used to

further breeding guidelines. 133 dogs were measured in several countries

using a standardised 'bony landmark' measuring system and photo analysis by

trained researchers. This paper describes two significant risk factors

associated with CM/SM in the skull shape of the CKCS:

extent of brachycephaly (the broadness of the cranium (top of skull)

relative to its length) and distribution of doming of the cranium. The study

showed that having a decreased cephalic index (less brachycephaly) was

significantly protective. Further to this, more cranium at the back of the

head (caudally) relative to the amount at the fro nt of the head (rostrally)

was significantly protective against disease development. This was shown at

three and five years of age, and also when comparing a sample of “SM clear”

individuals over five years to those affected under three years. This study

suggests that brachycephaly, with resulting rostrocaudal doming, is

associated with CM/SM. These results could provide a way for selection

against the risk head shape in the CKCS, and thus enable a

reduction in CM/SM incidence. Studying other breeds in which CM free

individuals are more frequent may validate this risk phenotype for CM too.

Use of Morphometric Mapping to Characterise Symptomatic Chiari-Like Malformation, Secondary Syringomyelia and Associated Brachycephaly in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. Susan P. Knowler, Chloe Cross, Sandra Griffiths, Angus K. McFadyen, Jelena Jovanovik, Anna Tauro, Zoha Kibar, Colin J. Driver, Roberto M. La Ragione, Clare Rusbridge. PLOS One. January 2017. Quote: Objectives: To characterise the symptomatic phenotype of Chiari-like malformation (CM), secondary syringomyelia (SM) and brachycephaly in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel [CKCS] using morphometric [the quantitative analysis of form, a concept that encompasses size and shape] measurements on mid-sagittal Magnetic Resonance images (MRI) of the brain and craniocervical junction. Methods: This retrospective study, based on a previous quantitative analysis in the Griffon Bruxellois (GB), used 24 measurements taken on 130 T1-weighted MRI of hindbrain and cervical region. Associated brachycephaly was estimated using 26 measurements, including rostral forebrain flattening and olfactory lobe rotation, on 72 T2-weighted MRI of the whole brain. Both study cohorts were divided into three groups; Control, CM pain and SM and their morphometries compared with each other. Results: Fourteen significant traits were identified in the hindbrain study and nine traits in the whole brain study, six of which were similar to the GB and suggest a common aetiology. The Control cohort [31 CKCS in the hindbrain study (HBS) and 16 CKCSs in the whole brain study (WBS)] had the most natural, wolf-like, skull conformation in terms of ellipticity. The CM pain cohort [28 CKCSs in HBS and 25 CKCSs in WBS] was characterised by increased brachycephaly with greatest rostral forebrain flattening, shortest basicranium and compensatory cranial height. However, in this cohort, an increased distance between the occiput and atlas provided fewer impediments to CSF dynamics at the foramen magnum and reduced the risk for SM. The SM cohort [71 CKCSs in HBS and 31 CKCSs in WBS] exhibited two conformation anomalies. ... Although the CKCS is recognised as having a brachycephalic skull [40], facial length is very varied in the breed, with the muzzle becoming fashionably shorter and more dorsally rotated (airorhynchy) in the last decade ... One phenotype variation was influenced by incongruities at the craniocervical junction and increased proximity of the dens producing a ‘concertina’ type flexure with medullary elevation. The other phenotypic variation was influenced by increased brachycephaly resulted in a ‘concertina’ type flexure similar to the CM pain cohort. However, both SM variations were characterised by an apparent reduction in caudal fossa volume which compromised the CSF dynamics in the spinal cord. Conclusion: Morphometric mapping provides a diagnostic tool for quantifying symptomatic CM, secondary SM and their relationship with brachycephaly. It might identify dogs at risk of SM and CM pain to improve diagnosis and make available a means for screening breeding dogs and provide estimated breeding values. It is hypothesized that CM pain is associated with increased brachycephaly and SM can result from different combinations of abnormalities of the forebrain, caudal fossa and craniocervical junction which compromise the neural parenchyma and impede cerebrospinal fluid flow.

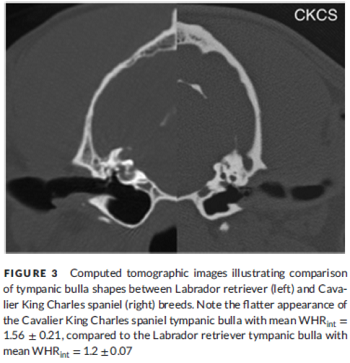

Computed tomographic morphometry of tympanic bulla shape and

position in brachycephalic and mesaticephalic dog breeds.

Ben Mielke, Richard Lam, Gert Ter Haar. Vet. Rad. & Ultra. July

2017. Quote: Anatomic variations in skull morphology have been

previously described for brachycephalic dogs; however there is

little published information on interbreed variations in tympanic

bulla morphology. This retrospective observational study aimed to

(1) provide detailed descriptions of the computed tomographic (CT)

morphology of tympanic bullae in a sample of dogs representing four

brachycephalic breeds (Pugs, French Bulldogs, English Bulldog, and

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels) versus two

mesaticephalic breeds (Labrador retrievers and Jack Russell

Terriers); and (2) test associations between tympanic bulla

morphology and presence of middle ear effusion. Archived head CT

scans for the above dog breeds were retrieved and a single observer

measured tympanic bulla shape (width:height ratio), wall thickness,

position relative to the temporomandibular joint, and relative

volume (volume:body weight ratio). A total of 127 dogs were sampled

[including 25 cavaliers]. Cavalier King

Charles Spaniels had significantly flatter tympanic bullae

(greater width:height ratios) versus Pugs, English Bulldogs,

Labrador retrievers, and Jack Russell terriers. French Bulldogs and

Pugs had significantly more overlap between tympanic bullae and

temporomandibular joints versus

other breeds.

[See Figure 3 at right.] All brachycephalic

breeds had significantly lower tympanic bulla volume:weight ratios

versus Labrador retrievers. Soft tissue attenuating material (middle

ear effusion) was present in the middle ear of 48/100 (48%) of

brachycephalic breeds, but no significant association was found

between tympanic bulla CT measurements and presence of this

material. Findings indicated that there are significant interbreed

variations in tympanic bulla morphology, however no significant

relationship between tympanic bulla morphology and presence of

middle ear effusion could be identified. ... Cavalier King

Charles Spaniels represent a unique subset of

brachycephalic animals as they were found to have significantly

flatter tympanic bullae (defined by width: height ratios) than other

brachycephalic breeds. There was a high percentage of

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels with soft tissue attenuating

material in the middle ear (68%), which may have falsely reduced the

internal measurements obtained, increasing width: height ratio

(internal) artifactually. However, given the fact that the lower

bound of the 95% confidence interval measurements for

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (width:height ratio

(internal) 1.47−1.65)) was greater than the upper bound for all

breeds (except the French Bulldog which also had a high percentage

of material in middle ear (80%)), authors believe it is likely that

these measurements represented real changes present in this breed.

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels have been described

to have a unique disease resulting in the formation of a buildup of

highly viscous mucus within the middle ear (primary secretory otitis

media or otitis media with effusion) of dogs without clinical

evidence of otitis externa. It is thought that, due to a lack of

inflammation or signs of infection in the middle ear, the disease is

due to auditory tube dysfunction based on possible anatomical

changes of the middle ear or the auditory tube. The finding of an

anatomical variation in the shape of the tympanic bulla of

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels may offer a potential

explanation for the pathogenesis of this disease in addition to the

previously suggested changes in the orientation and function of the

auditory tube. However, given the lack of histopathology and

contrast-enhanced CT scan evaluations in the current study, this

hypothesis is speculative. Further investigation to identify

potential pathway alteration of the auditory tube in the

Cavalier King Charles Spaniel would be an interesting

addition for further clarification of this disease process.

other breeds.

[See Figure 3 at right.] All brachycephalic

breeds had significantly lower tympanic bulla volume:weight ratios

versus Labrador retrievers. Soft tissue attenuating material (middle

ear effusion) was present in the middle ear of 48/100 (48%) of

brachycephalic breeds, but no significant association was found

between tympanic bulla CT measurements and presence of this

material. Findings indicated that there are significant interbreed

variations in tympanic bulla morphology, however no significant

relationship between tympanic bulla morphology and presence of

middle ear effusion could be identified. ... Cavalier King

Charles Spaniels represent a unique subset of

brachycephalic animals as they were found to have significantly

flatter tympanic bullae (defined by width: height ratios) than other

brachycephalic breeds. There was a high percentage of

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels with soft tissue attenuating

material in the middle ear (68%), which may have falsely reduced the

internal measurements obtained, increasing width: height ratio

(internal) artifactually. However, given the fact that the lower

bound of the 95% confidence interval measurements for

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (width:height ratio

(internal) 1.47−1.65)) was greater than the upper bound for all

breeds (except the French Bulldog which also had a high percentage

of material in middle ear (80%)), authors believe it is likely that

these measurements represented real changes present in this breed.

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels have been described

to have a unique disease resulting in the formation of a buildup of

highly viscous mucus within the middle ear (primary secretory otitis

media or otitis media with effusion) of dogs without clinical

evidence of otitis externa. It is thought that, due to a lack of

inflammation or signs of infection in the middle ear, the disease is

due to auditory tube dysfunction based on possible anatomical

changes of the middle ear or the auditory tube. The finding of an

anatomical variation in the shape of the tympanic bulla of

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels may offer a potential

explanation for the pathogenesis of this disease in addition to the

previously suggested changes in the orientation and function of the

auditory tube. However, given the lack of histopathology and

contrast-enhanced CT scan evaluations in the current study, this

hypothesis is speculative. Further investigation to identify

potential pathway alteration of the auditory tube in the

Cavalier King Charles Spaniel would be an interesting

addition for further clarification of this disease process.

A genome-wide association study identifies candidate loci associated to syringomyelia secondary to Chiari-like malformation in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Frédéric Ancot, Philippe Lemay, Susan P. Knowler, Karen Kennedy, Sandra Griffiths, Giunio Bruto Cherubini, Jane Sykes, Paul J. J. Mandigers, Guy A. Rouleau, Clare Rusbridge, Zoha Kiba. BMC Genetics. March 2018;19:16. Quote: Background: Syringomyelia (SM) is a common condition affecting brachycephalic toy breed dogs and is characterized by the development of fluid-filled cavities within the spinal cord. It is often concurrent with a complex developmental malformation of the skull and craniocervical vertebrae called Chiari-like malformation (CM) characterized by a conformational change and overcrowding of the brain and cervical spinal cord particularly at the craniocervical junction. CM and SM have a polygenic mode of inheritance with variable penetrance. ... In the CKCS, risk of SM has been shown to be associated with increased brachycephaly with rostrocaudal doming i.e. a heightened cranium that slopes caudally [8] and reduced skull base due to craniosynostosis or premature skull suture closure. ... Results: We identified six cranial T1-weighted sagittal MRI measurements that were associated to maximum transverse diameter of the syrinx cavity. Increased syrinx transverse diameter has been correlated previously with increased likelihood of behavioral signs of pain. We next conducted a whole genome association study of these traits in 65 Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS) dogs (33 controls, 32 with extreme phenotypes). Two loci on CFA22 and CFA26 were found to be significantly associated to two traits associated with a reduced volume and altered orientation of the caudal cranial fossa. Their reconstructed haplotypes defined two associated regions that harbor only two genes: PCDH17 on CFA22 and ZWINT on CFA26. PCDH17 codes for a cell adhesion molecule expressed specifically in the brain and spinal cord. ZWINT plays a role in chromosome segregation and its expression is increased with the onset of neuropathic pain. Targeted genomic sequencing of these regions identified respectively 37 and 339 SNPs with significantly associated P values. Genotyping of tagSNPs selected from these 2 candidate loci in an extended cohort of 461 CKCS (187 unaffected, 274 SM affected) identified 2 SNPs on CFA22 that were significantly associated to SM strengthening the candidacy of this locus in SM development. Conclusions: We identified 2 loci on CFA22 and CFA26 that contained only 2 genes, PCDH17 and ZWINT, significantly associated to two traits associated with syrinx transverse diameter. The locus on CFA22 was significantly associated to SM secondary to CM in the CKCS dog breed strengthening its candidacy for this disease. This study will provide an entry point for identification of the genetic factors predisposing to this condition and its underlying pathogenic mechanisms.

Morphometric Analysis of Spinal Cord Termination in Cavalier King Charles spaniels. Courtney Sparks. ACVIM Forum, Abstract N-15. June 2018. Quote: Cavalier King Charles spaniels (CKCS) suffer from Chiari-like malformation (CM), a skull malformation that causes crowding of the caudal fossa, and syringomyelia (SM). Affected dogs show signs of pain and frequently show lumbosacral pain. Tethered cauda equina has been reported in people with CM but currently there is no morphometric data on the caudal aspect of the vertebral column and spinal cord in CKCS. The purpose of this study was to compare the location of the conus medullaris in CKCS with other size-matched breeds. We hypothesized that the spinal cord terminates more caudally in CKCS. A retrospective study was conducted on 90 dogs with thoracolumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Dog breeds were grouped as CKCS (n=48), and brachycephalic (n=21) and non-brachycephalic (n=20) size-matched controls. ... Cavalier King Charles Spaniels are classified as a brachycephalic breed and this classification is considered important in morphometric analyses of their skull and brain. ... MRI identifiers were removed to blind the observer. Termination of the spinal cord was determined from T2-weighted sagittal and axial images as the 6th (L6), or 7th lumbar vertebra (L7), or sacrum. Breed was revealed after Chi-squared analyses were performed. Among 48 CKCS, the spinal cord terminated at L6 in 3, L7 in 23, and sacrum in 22 dogs compared with 8 at L6, 27 at L7 and 5 at sacrum in 41 controls. Spinal cord termination was significantly more caudal in CKCS as compared to brachycephalic (P = 0.015) and non-brachycephalic breeds (P = 0.005). There was no difference between size-matched controls (P = 0.157). There is a need to investigate whether tethering of the cauda equina contributes to signs of pain in CKCS.

CONNECT WITH US