Atrioventricular Block in the

Cavalier King Charles Spaniel

Atrioventricular (AV) block is a slow or erratic heartbeat due to a malfunction of the electrical system of the dog's heart. While cavalier King Charles spaniels, as a breed, are not considered "predisposed" to AV block, several veterinary journal articles have reported it in CKCSs.

What It Is

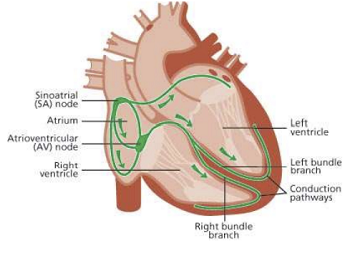

The dog's heart is combination of muscles which act as a pump. It pumps by contracting and expanding as the blood flows through it, starting at the atria (atriums) to the ventricles. The heart includes an electrical system which controls the frequency of the rate at which the heart contracts (systole) and relaxes (diastole) as it pumps blood into the arteries to the body. This cardiac electrical conduction system produces impulses to stimulate the heart muscles to perform a timely pumping action producing the heart beat.

A set of cells in the right atrium, called the

sinoatrial node (sinus

or SA node) generates electrical impulses and transmits them through

special fibers to the atrioventricular node (AV node) and to other

locations throughout the four chambers. The SA node is the heart's

normal pacemaker. The atrioventricular node receives the impulses and

then directs them on to the ventricles. This process allows for the two

atria to eject blood through the tricuspid and mitral valves into the

ventricles just before the ventricles contract to force the blood along

its intended path. The AV node also may become the heart's pacemaker, if

the SA node becomes unable to perform that function, for whatever

reason.

A set of cells in the right atrium, called the

sinoatrial node (sinus

or SA node) generates electrical impulses and transmits them through

special fibers to the atrioventricular node (AV node) and to other

locations throughout the four chambers. The SA node is the heart's

normal pacemaker. The atrioventricular node receives the impulses and

then directs them on to the ventricles. This process allows for the two

atria to eject blood through the tricuspid and mitral valves into the

ventricles just before the ventricles contract to force the blood along

its intended path. The AV node also may become the heart's pacemaker, if

the SA node becomes unable to perform that function, for whatever

reason.

Atrioventricular (AV) block occurs when, for whatever reason, electrical transmission through the AV to the ventricles is delayed or blocked. There are three "degrees" of AV block severity:

• First-degree AV block is the mildest form, in which the timing of electrical conduction is abnormally delayed but ultimately is transmitted.

• Second-degree AV block is intermittent transmission. In this case, the AV node allows some of the impulses to travel on to the ventricles, but blocks others of them. This form of AV block is subdivide into types I, II, A, B, and High-Grade, based upon severity and effects.

• Third-degree AV block, also known as complete AV block, occurs when no electrical impulses are conducted into the ventricles.

RETURN TO TOP

Causes

Each degree of AV block (first, second, third) may have a variety of different causes. They can be functional, meaning due primarily to the node(s), or secondary, meaning affected by causes apart from the nodes themselves. Here are some examples of each:

• First-degree: A high vagal tone (impulses from the vagus nerve that produce an inhibition in the heart beat), calcium deficiency, degenerative conduction system diseases particularly in older dogs of certain breeds (e.g., cocker spaniels and dachshunds), drug toxicity (particularly atropine. digoxin, bethanechol, physostigmine, and pilocarpine).

• Second-degree: Fibrosis (scarring of heart tissues), degeneration of the AV node, infection of the heart muscles, infection of the aortic valve, myocarditis (inflammatory cardiomyopathy), endocarditis (inflammation of the inner lining of the heart muscles), other forms of cardiomyopathy, electrolyte abnormalities, neurologic disorders, gastrointestinal, respiratory, bladder, or ocular disease, exposure to certain toxins, drug toxicity (particularly digoxin), trauma.

• Third-degree: Congenital heart defects, fibrosis (scarring of heart tissues), myocarditis (inflammatory cardiomyopathy), endocarditis (inflammation of the inner lining of the heart muscles), amyloidosis (protein-based deposits in the heart), cancer, electrolyte abnormalities, exposure to certain toxins, drug toxicity (particularly digitalis), stroke (myocardial infarction), age-related degeneration within the heart, and unknown.

Since AV blocks have been observed to switch from one degree to another, these causes cannot be definitively classified in only one degree or another.

RETURN TO TOP

Symptoms

Outward signs of AV block will vary greatly, and in many cases of first-degree and mild second-degree, the dog may display no symptoms at all. Typical symptoms of high-grade second-degree and third-degree AV include:

• Lethargy

• Exercise intolerance

• Weakness

• Coughing

• Breathing difficulties

• Slow heart rate (bradycardia)

• Collapse (pre-syncope)

• Fainting (syncope)

• Loss of appetite

• Vomiting

• Diarrhea

• Other signs of low-cardiac output

Most all of these outward signs could be attributed to any of several other disorders, especially mitral valve disease (MVD) in cavaliers. Therefore, thorough diagnosis is necessary to pinpoint the actual cause of the symptoms and eliminate other disorders with the same symptoms.

RETURN TO TOP

Diagnosis

Since many symptoms are common to many other disorders, the diagnosis modalities may be widespread, to either identify underlying causes or to eliminate them from consideration. Diagnostic techniques include the usual "clinical workup" of blood and urinalysis tests, along with chest x-rays, electrocardiography, echocardiography, possibly abdominal ultrasonography, and an atropine challenge test, a noninvasive means for confirming the location of certain types of second-degree AV blocks.

RETURN TO TOP

Treatment

Dogs diagnosed with first-degree and mild second-degree AV block, and showing no symptoms, may need no treatment at all, but should continue to be observed for worsening of their conditions.

In cases of high-grade second-degree AV block and all third-degree AV

block patients, rarely is any medication successful in treating the

disorder. Drugs may be prescribed to treat the underlying causes in

which AV block is

a secondary consequence, such as anti-inflammatory

glucocorticoids. Emergency treatments with such drugs as intravenous

dopamine, cobutamine, or isoproterenol may do more harm than good, by

provoking ventricular tachyarrhythmias or vasodilation.

a secondary consequence, such as anti-inflammatory

glucocorticoids. Emergency treatments with such drugs as intravenous

dopamine, cobutamine, or isoproterenol may do more harm than good, by

provoking ventricular tachyarrhythmias or vasodilation.

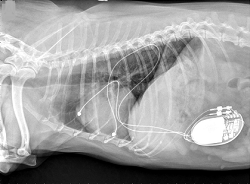

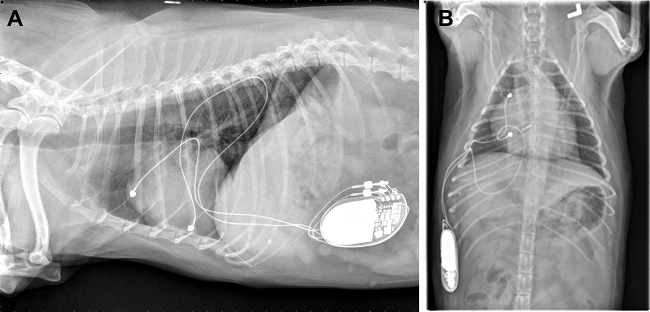

The most effective long-term care for symptomatic second-degree AV block and third-degree AV block cases has been found to be the surgical insertion of an artificial pacemaker (right, above).

The presence of mitral valve disease in the dog may pose an

additional difficulty in implanting a permanent pacemaker. In

a

June 2015 article, Colorado State Univ. cardiologists

reported the case of a seven-year-old female cavalier l diagnosed with third-degree AV block and both

severe regurgitation through the mitral and tricuspid valves and severe

right atrial and right ventricular dilation and heart failure, and

moderate

pulmonary hypertension, all due to degenerative valve diseases.

She was treated with a permanent artificial cardiac pacemaker and, due

to the severe structural heart disease and heart failure present, a dual

chamber pacemaker system was recommended in attempt to optimize cardiac

performance by maintaining AV synchrony and heart rate variability.

(See an x-ray of her at left.) Because of the severely enlarged right chambers, dual chamber pacing

with epicardial lead placement was recommended. The dog was rechecked at

7 months following implantation, and the owners reported complete

resolution of clinical signs and an increase in the dog’s activity. The

pacemaker required no change in settings.

pulmonary hypertension, all due to degenerative valve diseases.

She was treated with a permanent artificial cardiac pacemaker and, due

to the severe structural heart disease and heart failure present, a dual

chamber pacemaker system was recommended in attempt to optimize cardiac

performance by maintaining AV synchrony and heart rate variability.

(See an x-ray of her at left.) Because of the severely enlarged right chambers, dual chamber pacing

with epicardial lead placement was recommended. The dog was rechecked at

7 months following implantation, and the owners reported complete

resolution of clinical signs and an increase in the dog’s activity. The

pacemaker required no change in settings.

In an August 2020 article, UK cardiology clinicians report the case of a 4 year old cavalier diagnosed with third-degree AV block and was anethesized for implant of a permanent artifical placemaker. During that procedure, the dog's heart stopped (a ventricular standstill), at which point the clinicians immediately began temporary transcutaneous pacing (TCP) at 80 beats-per-minute. Once the permanent pacemaker (pulse generator) was installed and operational, the TCP was ended. They concluded with the recommendation that when anesthesizing dogs with third-degree AV block, "an appropriate and effective means of temporary pacing must be in place."

RETURN TO TOP

Research News

October 2022:

20-month old cavalier with third-degree artioventricular block

has pacemaker inserted at CVCA.

In

an

October 2022 press release, CVCA Cardiac Care for Pets in Virginia

reported on the successful surgery to insert an artificial pacemaker in

a 20-month old cavalier, Henry (right), which had been diagnosed

with third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block. Cardiologists Sarah Holdt

and Neal Peckens performed diagnosis and the surgery. Henry's heart rate

prior to surgery was 35 beats per minute, while a healthy heart at his

age should have been beating around 120 beats per minute, according to

the article. During the surgery, Henry's heart stopped beating for eight

minutes, and the veterinarians and technician teams began performing CPR

and after defibrillation, they were able to start his heart again.

In

an

October 2022 press release, CVCA Cardiac Care for Pets in Virginia

reported on the successful surgery to insert an artificial pacemaker in

a 20-month old cavalier, Henry (right), which had been diagnosed

with third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block. Cardiologists Sarah Holdt

and Neal Peckens performed diagnosis and the surgery. Henry's heart rate

prior to surgery was 35 beats per minute, while a healthy heart at his

age should have been beating around 120 beats per minute, according to

the article. During the surgery, Henry's heart stopped beating for eight

minutes, and the veterinarians and technician teams began performing CPR

and after defibrillation, they were able to start his heart again.

August 2020:

Cavalier with third-degree atrioventricular block and heart

stoppage required a

temporary

pacemaker during surgery. In an

August 2020 article, UK cardiology clinicians (Lucy Miller, Miguel

Gozalo-Marcilla [right], Geoff Culshaw, Ambra Panti) report the

case of a 4 year old cavalier King Charles spaniel diagnosed with

third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block and was anethesized for implant

of a permanent artifical placemaker. During that procedure, the dog's

heart stopped (a ventricular standstill), at which point the clinicians

immediately began temporary transcutaneous pacing (TCP) at 80

beats-per-minute. Once the permanent pacemaker (pulse generator) was

installed and operational, the TCP was ended. They concluded with the

recommendation that when anesthesizing dogs with third-degree AV block,

"an appropriate and effective means of temporary pacing must be in

place."

temporary

pacemaker during surgery. In an

August 2020 article, UK cardiology clinicians (Lucy Miller, Miguel

Gozalo-Marcilla [right], Geoff Culshaw, Ambra Panti) report the

case of a 4 year old cavalier King Charles spaniel diagnosed with

third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block and was anethesized for implant

of a permanent artifical placemaker. During that procedure, the dog's

heart stopped (a ventricular standstill), at which point the clinicians

immediately began temporary transcutaneous pacing (TCP) at 80

beats-per-minute. Once the permanent pacemaker (pulse generator) was

installed and operational, the TCP was ended. They concluded with the

recommendation that when anesthesizing dogs with third-degree AV block,

"an appropriate and effective means of temporary pacing must be in

place."

June 2015:

Cavalier with third-degree atrioventricular block and mitral

valve disesase receives dual chamber pacemaker.

In

a

June 2015 article, Colorado State Univ. cardiologists Christian

Weder, Eric Monnet, Marisa Ames, and Janice Bright (right)

reported the case of a seven-year-old female cavalier King Charles

spaniel diagnosed with third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block and both

severe regurgitation through the mitral and tricuspid valves and severe

right atrial and right ventricular dilation and heart failure, and

moderate pulmonary hypertension, all due to degenerative valve diseases.

She had a four-day history of lethargy, exercise intolerance, and

decreased appetite with a very low heart rate of 40 beats-per-minute.

She was treated with a permanent artificial cardiac pacemaker and, due

to the severe structural heart disease and heart failure present, a dual

chamber pacemaker system was recommended in attempt to optimize cardiac

performance by maintaining AV synchrony and heart rate variability.

Because of the severely enlarged right chambers, dual chamber pacing

with epicardial lead placement was recommended. The dog was rechecked at

7 months following implantation, and the owners reported complete

resolution of clinical signs and an increase in the dog’s activity. The

pacemaker required no change in settings.

In

a

June 2015 article, Colorado State Univ. cardiologists Christian

Weder, Eric Monnet, Marisa Ames, and Janice Bright (right)

reported the case of a seven-year-old female cavalier King Charles

spaniel diagnosed with third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block and both

severe regurgitation through the mitral and tricuspid valves and severe

right atrial and right ventricular dilation and heart failure, and

moderate pulmonary hypertension, all due to degenerative valve diseases.

She had a four-day history of lethargy, exercise intolerance, and

decreased appetite with a very low heart rate of 40 beats-per-minute.

She was treated with a permanent artificial cardiac pacemaker and, due

to the severe structural heart disease and heart failure present, a dual

chamber pacemaker system was recommended in attempt to optimize cardiac

performance by maintaining AV synchrony and heart rate variability.

Because of the severely enlarged right chambers, dual chamber pacing

with epicardial lead placement was recommended. The dog was rechecked at

7 months following implantation, and the owners reported complete

resolution of clinical signs and an increase in the dog’s activity. The

pacemaker required no change in settings.

RETURN TO TOP

RETURN TO TOP

Veterinary Resources

Ventricular septal defect repair in a small dog using cross-circulation. G. B. Hunt, M. R. B. Pearson, C. R. Bellenger, R. Malik. Australian Vet. J. October 1995; doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1995.tb06175.x. Quote: A haemodynamically significant ventricular septal defect was diagnosed in a 3-month-old male Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. A median sternotomy was performed and the 6.5 kg dog placed on cardiopulmonary bypass using pump-assisted cross-circulation. A 10 mm diameter peri-membranous ventricular septal defect was closed using a continuous suture of 4–0 polypropylene, via a 2.5 cm incision in the right ventricular outflow tract. ... Atrial contractions resumed soon after the aortic clamp was released, but complete atrioventricular (AV) block resulted in ventricular asystole. ... After twenty minutes of partial bypass, 1 : 1 AV conduction returned spontaneously, although right bundle branch block was evident in the surface electrocardiogram. ... The dog was haemodynamically stable until 7 h after surgery, when it suffered a sustained episode of complete AV block. ... A temporary pacing electrode was inserted into the right ventricular apex via an external jugular vein, but conducted sinus rhythm with first-degree AV block resumed during the procedure. ... Nineteen hours after surgery a further short episode (10 min) of third-degree AV block was noted, and reverted to normal sinus rhythm after administration of atropine. ... Two months after surgery the dog was clinically normal and had gained 3 kg in weight. The owners considered its exercise tolerance had improved and reported that it was now more active than it had been before surgery. Fremitus was no longer palpable, and the original systolic murmur was replaced by a soft systolic murmur audible over the region of the tricuspid valve. The electrocardiogram revealed persistent right bundle branch block. ... The persistent right bundle branch block was probably related to the proximity of the IVSD repair to the atrioventricular conduction system (Wilcox and Anderson 1992). Likewise, the self-terminating episodes of thirddegree AV block probably resulted from temporary inflammation or ischaemia. ... The duration of cardiopulmonary bypass was 90 minutes. Complications in the immediate postoperative period were mild and easily managed.

Advanced Electrocardiographic Parameters Change with Severity of Mitral Regurgitation in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels in Sinus Rhythm. M. Špiljak Pakkanen, A. Domanjko Petrič , L.H. Olsen, A. Stepančič, T.T. Schlegel, T. Falk, C.E. Rasmussen, V. Starc. J. Vet. Intern. Med. January 2012; doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00845.x. Quote: Background: Multiple advanced resting ECG (A-ECG) techniques have improved the diagnostic or prognostic value of ECG in detecting human cardiac diseases even before onset of clinical signs or changes in conventional ECG. Objective: To determine which A-ECG parameters, derived from 12-lead A-ECG recordings, change with severity of mitral regurgitation (MR) caused by myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCSs) in sinus rhythm. Animals: ... In this cross-sectional study, 99 privately owned CKCSs were examined. All dogs underwent clinical examination, cardiac auscultation, echocardiography, and high fidelity approximately 5-minute 12-lead ECG. A-ECG was performed after approximately 5 minutes of acclimation, 20 minutes of echocardiography, and 5 minute of additional rest in a quiet environment at all study sites. None of the dogs were sedated for examination. All of the dogs were echocardiographically free of other cardiac diseases and with no clinical signs of systemic disease. Twenty-three CKCSs were excluded because of insufficient quality of ECG recording (n = 10), premature atrial depolarizations (n = 8), 2nd degree AV block (n = 3), 2nd degree sinoatrial block (n = 1), or euthanasia before completion of all study measures (n = 1). ... Seventy-six privately owned CKCSs. Methods: Dogs were prospectively divided into 5 groups according to the degree of MR (estimated by color Doppler mapping as the percentage of the left atrial area affected by the MR jet) and presence of clinical signs. High fidelity approximately 5-minute 12-lead ECG recordings were evaluated using custom software to calculate multiple conventional and A-ECG parameters. Results: Nineteen of 76 ECG parameters were significantly different across the 5 dog groups. A 4-parameter model that incorporated results from 1 parameter of heart rate variability, 2 parameters of QT variability, and 1 parameter of QRS amplitude was identified that explained 82.4% of the variance with a correlation coefficient (R) of 0.60. When age or murmur grade was included in the statistical model the prediction value further increased the R to 0.74 and 0.85, respectively. Conclusion: In CKCSs with sinus rhythm, 4 selected A-ECG parameters further improve prediction of MR jet severity beyond age and murmur grade, although the predictive increment in this study probably is not sufficient to warrant utilization in clinical veterinary practice.

Permanent dual chamber epicardial pacemaker implantation in two dogs with complete atrioventricular block. Christian Weder, Eric Monnet, Marisa Ames, Janice Bright. J. Vet. Cardiol. June 2015; doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2014.11.002. Quote: Between November 2013 and December 2013, two dogs with complete atrioventricular (AV) block had a permanent, dual chamber epicardial pacing system implanted. Steroid-eluting unipolar, button-type epicardial leadsa were sutured to the right atrial appendage and right ventricular wall via a right thoracotomy in both dogs. The pacemakers were programmed in VDD mode. Permanent dual chamber epicardial pacemaker implantation was successful in both dogs with no intra-operative complications. One dog had an acute onset of neurologic signs two days post-operatively that resolved within 24 h. Both dogs have had complete resolution of the clinical signs related to the bradyarrhythmia, and one dog has had complete resolution of chylothorax. One dog had a major lead complication characterized by intermittent loss of capture that resolved by increasing the pacemaker output. Based on the outcome of these two cases, implantation of permanent dual chamber epicardial pacing systems is possible in dogs providing an alternative to dual chamber transvenous systems. ... Case 1: A seven-year-old spayed female Cavalier King Charles spaniel was referred to the cardiology service at the Colorado State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital for evaluation of an approximately four-day history of lethargy, exercise intolerance, and decreased appetite with an inappropriate bradycardia (heart rate = 40 bpm). Initial diagnostics included an ECG, echocardiogram, Doppler blood pressure, complete blood count, biochemical profile, thoracic radiography, and urinalysis. Testing for heartworm, Lyme disease, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Ehrlichia canis, Ehrlichia ewingii and Anaplasma platys was also done. The ECG showed third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block with a ventricular escape rhythm that was unresponsive to atropine (0.04 mg/kg SQ; no AV nodal conduction noted post atropine). The Doppler echocardiogram showed degenerative mitral valve disease (ACVIM stage B2), degenerative tricuspid valve disease with severe tricuspid regurgitation, severe right atrial and right ventricular dilation, and moderate pulmonary hypertension. ... Treatment with a permanent artificial cardiac pacemaker was advised and, due to the severe structural heart disease and heart failure present, a dual chamber pacemaker system was recommended in attempt to optimize cardiac performance by maintaining AV synchrony and intrinsic heart rate variability. Furthermore, the risk of lead dislodgement, intracardiac thrombus, and myocardial perforation were deemed considerable with transvenous pacing due to the severe right ventricular dilation. For these reasons, dual chamber pacing with epicardial lead placement was recommended. ... The dog was rechecked again at 7 months postimplantation and the owners reported complete resolution of clinical signs and an increase in the dog’s activity. Interrogation of the pacemaker at this time showed appropriate atrial and ventricular sensing as well as appropriate pacing and capture. No pacemaker settings were changed. Thoracic radiographs obtained at this visit confirmed correct position of both leads (Fig. 1) [See Figure 1, below].

Successful transcutaneous pacing following ventricular standstill during anaesthetic induction in a dog with third-degree atrioventricular block. Lucy Miller, Miguel Gozalo-Marcilla, Geoff Culshaw, Ambra Panti. Vet. Rec. Case. Rpt. August 2020; doi: 10.1136/vetreccr-2020-001146. Quote: Third-degree atrioventricular block is a haemodynamically unstable bradycardia frequently resulting in signs of lethargy, weakness and collapse. In this reported case, a four year-four month-old male neutered Cavalier King Charles spaniel diagnosed with third-degree atrioventricular block was referred for transvenous permanent pacemaker implantation. During induction of general anaesthesia, the dog suffered cardiac arrest consistent with ventricular standstill, as indicated by cessation of ventricular electrical activity on the ECG monitor and the absence of a peripheral pulse. The prior placement of transthoracic pacing pads under sedation allowed for rapid commencement of temporary transcutaneous pacing and proved effective in achieving ventricular capture with re-establishment of cardiac output. The subsequent general anaesthesia for implantation of a permanent pacemaker was uneventful. This report considers the possible causes of ventricular escape rhythm suppression and highlights the importance of ensuring availability of a temporary pacing method from the outset when anaesthetising animals with unstable and symptomatic bradycardias.

Clinical and Echocardiographic Findings in an Aged Population of Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Jorge Prieto Ramos, Andrea Corda, Simon Swift, Laura Saderi, Gabriel De La Fuente Oliver, Brendan Corcoran, Kim M. Summers, Anne T. French. Animals. March 2021; doi: 10.3390/ ani11040949. Quote: Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is the most common cardiac disease in dogs. It varies from dogs without clinical signs to those developing left-sided congestive heart failure, leading to death. Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCSs) are particularly susceptible to MMVD. We hypothesised that within the elderly CKCS population, there is a sub-cohort of MMVD-affected dogs that do not have cardiac remodelling. The objectives of the present study were (i) to determine the prevalence and the degree of cardiac remodelling associated with MMVD; and (ii) assess the effect of age, gender, and body weight on echocardiographic status in a population of aged CKCSs. A total of 126 CKCSs ≥ 8 years old were prospectively included. They all had a physical and echocardiographic examination. A systolic murmur was detected in 89% of dogs; the presence of clinical signs was reported in 19% of them; and echocardiographic evidence of MMVD was described in 100%. ... During echocardiographic examinations, arrhythmic events were observed in 11 dogs, and included supraventricular premature complexes (n = 6; 4.8%), second degree atrioventricular block (n = 3; 2.4%), ventricular premature complexes (n = 1; 0.8%), and sinus arrest (n = 1; 0.8%). ... Despite the high prevalence, 44.4% of the dogs were clear of echocardiographic signs of cardiac remodelling. Age was significantly associated with the presence and severity of cardiac remodelling and mitral valve prolapse. Our results showed that a proportion of elderly CKCS with confirmed MMVD did not undergo advanced stages of this pathology.

Heart rate distribution in dogs with third degree atrioventricular block and rate responsive pacemakers. A. Pires, S. Raheb, G. Monteith, M. E. Colpitts, A. Chong, M. L. O’Sullivan, S. Fonfara. J. Vet. Cardiol. October 2022; doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2022.07.001. Quote: Introduction: In dogs, single lead ventricular pacing, ventricular sensing, inhibition response, rate adaptive (VVIR) pacemakers are routinely used to treat third degree atrioventricular block. The objectives of this study were to investigate the heart rate distribution in dogs with VVIR pacemakers, and report changes when activity settings were adjusted. Animals: Eighteen client-owned dogs with VVIR pacemakers for third degree atrioventricular block [including two Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (11%)]. Materials and methods: This observational study consisted of a review of medical records of dogs with VVIR pacemakers. For dogs with >50% of paced beats at the lower pacing rate, the activity daily living (ADL) and exertion responses were increased. Re-evaluations were performed after 6–12 months. Results: Heart rate distribution similar to healthy dogs was absent for all dogs. In nine dogs, the ADL and exertion responses were increased to the highest level. Of these, three dogs showed no improvement in heart rate distribution; for two dogs, one with an epicardial pacemaker, several activity settings were adjusted and pacing at higher heart rates was observed at re-evaluation. Four dogs died or were lost to follow-up. Clinical signs had resolved for all dogs after pacemaker implantation. Conclusion: Default activity settings of VVIR pacemakers do not result in heart rate distribution equivalent to healthy dogs. Increasing the ADL and exertion response settings to the highest levels did not improve the pacemaker rate response. Further investigations into the role of dog size, generator positioning, pacemaker settings, and whether rate responsiveness is required for dogs' quality and quantity of life are warranted.

CONNECT WITH US